The Afghan Women Journalists Defying the Taleban

Against all odds and despite constant danger, a brave few continue to report.

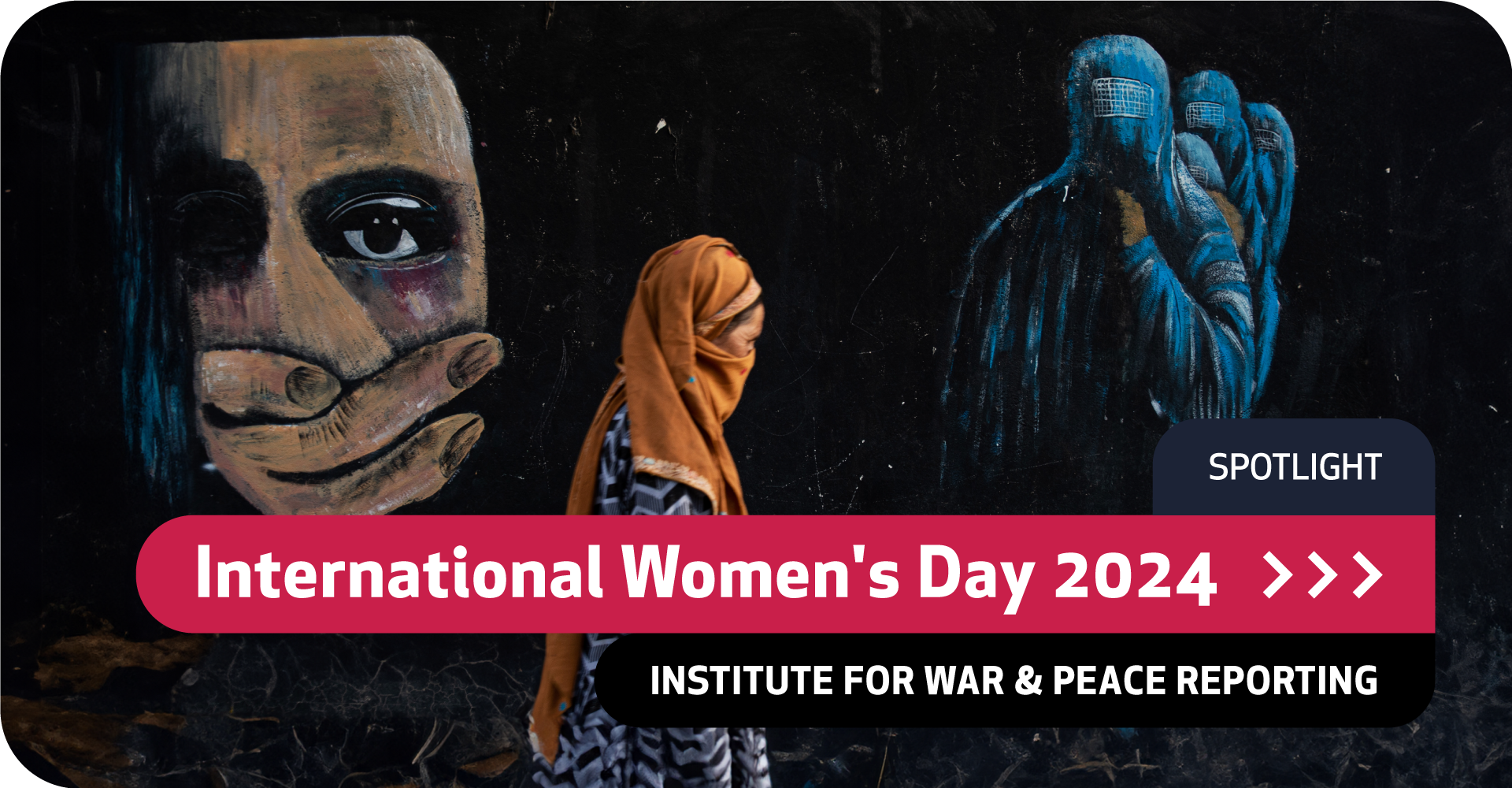

Since the Taleban takeover of August 2021, conditions for Afghan girls and women have deteriorated dramatically. The authorities have imposed oppressive policies that curtail freedom of movement, expression and association.

More than 80 per cent of female journalists have lost their jobs, according to Reporters Without Borders. The few who remain must navigate intimidation and grave threats to their security to continue working.

The names and exact locations of the women profiled here have been changed to protect their identities.

Shafiqa

Shafiqa recalls waking before dawn on the morning of August 15, 2021, in her home in a central province of Afghanistan. The 29-year-old immediately checked her phone to see if the rumours that had been circulating the previous day were true. To her dismay, the first thing she saw was a Facebook video of Taleban forces that had entered the city the night before.

“Life turned into darkness” at that moment, the mother-of one said.

She immediately began sifting through her treasured archive of bylined clippings from her work as a journalist specialising in women’s issues. For her own safety, she decided to burn them in a corner of her building’s courtyard.

“Life turned into darkness.”

The next day, veiled completely in black, she attempted to return to the newspaper offices where she worked to retrieve her personal belongings and documents.

There, she was confronted by complete devastation; everything had been looted. As she tried to leave, a Taleban policeman saw her and gave chase.

“I ran until I reached a dead-end alley and entered a house,” she said. She stayed in hiding for a week before relocating to Kabul. There, in a small room on the outskirts of the capital, she continues to work as a journalist, using a pseudonym to write about the struggles Afghan women were facing.

In the first six months after the Taleban takeover, Shafiqa received numerous online threats, including videos of beheadings and murders sent to her phone from anonymous numbers.

Shafiqa finally emailed all the online sites she had written for, asking them to delete her name and articles. Laughing bitterly, she said, “When I became a reporter without identity and face, even the Taleban forgot about me.”

She then started working under a pseudonym for a local media outlet now operating outside the country. This, too, was fraught with danger.

“Looking for information can cost a journalist her life.”

“Looking for information can cost a journalist her life,” said Shafiqa, recalling how she was forcibly dragged out of a Kabul store when she dared film Taleban officials threatening and abusing a female shopkeeper.

Every day, she has to pass through Taleban security checkpoints where she is stopped and interrogated. She is asked who she is, where she is going, why she is unaccompanied and has her modesty critiqued.

And even basic reporting is a challenge. Now, Shafiqa said, “People are not willing to share even the smallest piece of information with journalists because everyone is afraid that their information might leak to the Taleban.”

For the reporters themselves, the risks are immense, she continued, adding, “Female journalists publishing a report,must be accountable to the Taleban for every word, and if they fail to answer, they are threatened with death.”

Shafiqa can barely make enough to support her and her small daughter and admits to having contemplated suicide. But she is driven by her desire to continue raising awareness about women’s issues, particularly violence against them, for as long as she can.

Hila

Hila, a 25-year-old former law student in Nangarhar province, describes her life as a struggle in darkness. She wakes up early and closets herself in a small room with her books, computer and secret phone. Only her mother and sisters know that she continued working as a journalist after the Taleban retook power; the male members of her family are unaware.

When Hila began working at a Nangarhar broadcaster in 2018, she also kept it a secret from male family members. She broke the television at home the day before her first programme aired so that her father would not recognise her voice.

“Everything has changed for women, they are no longer treated as human beings.”

After a few months her male family members found out about her work and threatened her to stop immediately. One of her brothers stood up for her and insisted she continue.

On the night of August 14, 2021, as the Taliban approached the city, she and her handful of female colleagues stayed awake all night texting each other in terror.

Three days later she ventured out for the first time and recalled, “The whole city was strangely quiet. It was as if a suicide bomber had killed a large number of people.”

Even wrapped in a black burqa, she felt vulnerable as the only woman in the scorching heat. So she returned home again.

Hila was terrified of suffering the same fate as her mother, who told her that under the first Taleban regime she had not been able to leave the house for five years.

“They did not allow girls and women to study, and we could not even go to the city,” her mother said.

Hila was eventually contacted by her university, inviting her to return for her final year of law school. But once there she found herself confined to a classroom boxed in with wooden boards as the only female student. She could not even see the professor. When Hila asked a question, instead of receiving an answer, she was met with remarks like, “When you speak to me, your voice must be soft.”

"The days of democracy are over.”

After six months of unemployment, in January 2022 she started working for a news agency, but could tell no-one except her mother that she had resumed work. Any friend or acquaintance could be a Taleban spy; social trust had vanished.

“Everything has changed for women,” Hila said. “They are no longer treated as human beings.”

Hila now writes under a pseudonym for a local media outlet, but sometimes needs access to Taleban government sources for security reports. This is fraught with danger; her enquires are met with misogynistic threats.

She recalled a Taleban official telling her, “A Muslim woman doesn’t work. She stays at home. The days of democracy are over,” before he hung up. She stayed awake all that night with her mother and sisters, fearing that Taleban soldiers might raid their home to arrest her.

“By doing this, you are signing your own death warrant, and your father is unaware,” her mother told her.

But despite the dangers, Hila says that she is happy to be working, remembering the days when she did not even dare leave the house.

Leila

When the Taleban took over Kabul, Leila was studying Persian literature at Kabul University and working as a radio presenter.

The 23-year-old spent two months hiding at home, fearful over rumours that the militants were marrying off young girls to their soldiers – until her office emailed to request she return.

She now works for one of the Taleban-controlled media outlets in Kabul and described the office atmosphere as like being under siege. Leila and her three other female colleagues work in a small, dark room, fully veiled and with no face-to-face communication with their male colleagues.

"Leila was held for two hours and accused of being a spy."

As a reporter, Leila needs to go out into the city and attend press conferences, but despite having a Taleban work permit has often been threatened, insulted and denied access to official events.

Taleban officers often supervise her meetings, preventing interviewees from criticising the regime.

“If we say anything against them, neither us nor our camera will remain [unbroken],” she continued.

At one press conference at Kabul Medical University, Taleban officials asked her driver, “Wasn’t there anyone else in your office that you have brought a girl?”

After permitting her male cameraman to enter the venue, they made her wait for half an hour before allowing her entry - but guards instructed her to sit in a corner where she would not be visible.

"Our presence in the media is crucial."

At another event in January 2022, Taleban forces detained her and her cameraman, beating and interrogating him before taking them both to the police station. Leila was held for two hours and accused of being a spy.

Nonetheless, Leila insists that she will continue to work, no matter how dire the conditions, because “our presence in the media is crucial”.

Zainab Pirzad is an IWPR media consultant and mentor working with Afghan women journalists. She was one of the founding members and editor of Rukhshana, the first women-for-women media in Afghanistan