Ukraine: Justice on the Frontlines

Kharkiv investigators bring skills, technology and perseverance to the risky task of documenting war crimes.

Ukraine: Justice on the Frontlines

Kharkiv investigators bring skills, technology and perseverance to the risky task of documenting war crimes.

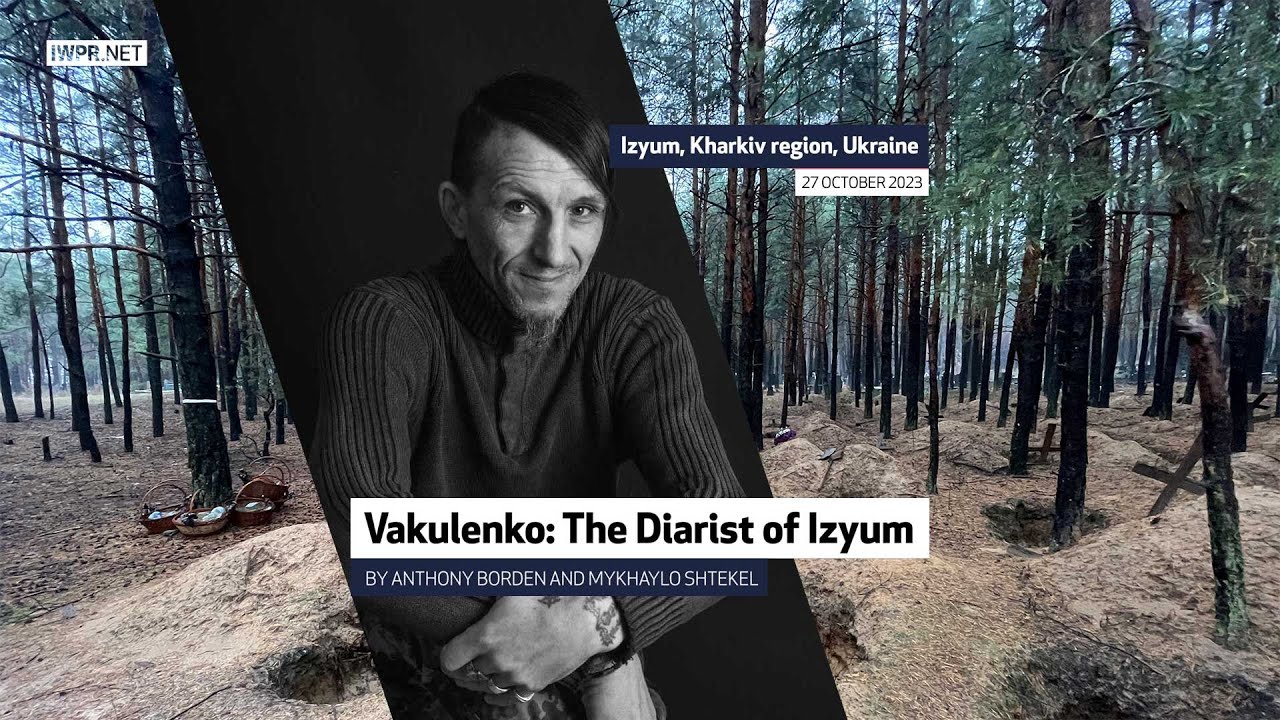

Without a box or a bag, the 449 bodies laid in the mass grave site in Izyum were placed in the sandy ground directly, to give them some interim place of rest. A year after liberation, 48 bodies are still unidentified.

The remains from grave number 319 were so degraded that upon exhumation it was impossible to determine the gender. Yet after extensive investigation, Kharkiv police identified not only the victim – Volodymyr Vakulenko, a renowned children’s writer – but also the alleged perpetrators.

Investigations are, meanwhile, continuing on Groza, where 59 mourners were killed on October 5 by an Iskandar missile, based on a suspected tip-off from two former village residents now living in Russia.

And every day another shell lands in Kharkiv region – with more than 17 towns and villages reporting missile attacks on November 16 alone.

This is justice on the frontlines, Ukraine’s unique effort to investigate, charge and prosecute those responsible for war crimes even as the conflict continues.

“Two per cent of the Kharkiv region is still under occupation,” noted Oleksandr Filchakov, 44, chief regional prosecutor. “Every day, Kupiansk is under heavy fire. And every day police, security services and prosecutors are working there to document war crimes being committed.”

The prosecutor’s conference room displays cases under investigation, with printed panels running along three sides of the large hall. One details the shelling of the Shevchenko district, in May 2022, which killed nine people. A panel for the Groza attack, a month earlier, is already installed.

The total number of war crimes cases registered across Ukraine is now more than 113,000. Of that, more than 20,000 – nearly one-fifth – are in the Kharkiv region. These crimes, according to Filchakov, have resulted in more than 2,200 dead and over 3,200 wounded, with upwards of 1,000 people still missing. More than 800 people have reported been tortured, although it is believed that the real numbers are higher.

To date, 49 individuals, mostly Russian soldiers, have been arrested in the occupied areas and charged with war crimes. Of these, 14 cases have gone to trial involving 31 accused, with three cases completed and seven found guilty.

The shelling of civilian targets comprised up to 80 per cent of the total, according to Spartak Borisenko, 35, acting director of war crimes investigations in the Kharkiv prosecutor’s office. Then came cases of torture carried out in two dozen places of detention. These were followed by executions and murders, and then sexual violence and crimes against children.

“After the occupation, when we visited the de-occupied territories, we were shocked by the quantity of people killed, the quantity of war crimes we needed to investigate,” said Borisenko. His department was created at that time, and has grown to 22 positions, of which 17 are for prosecutors, though not all are currently filled.

At its height, the region was registering up to 2,000 new cases per month, with that figure now around 500.

The prosecution provides strategic guidance and tactical decision-making, with responsibility for designing and driving legal cases. Police are the main investigators, with the security services (SBU) focusing on attacks on military targets and security- and international related issues. Joint investigative groups are often formed. Military and medical experts are brought in analyse weaponry and ballistics, as well as wound types and causes of death.

In the case of Groza, the SBU has taken the lead in investigating the two suspects, who allegedly kept in close contact with villagers and provided information that allowed the Russian security services to target the large gathering of mourners.

The preponderance of shelling has created specific challenges. Securing evidence amid the chaos of a strike is difficult, and the constant development of armaments means that damage from new weapons can be hard to analyse. This is especially important in confirming war crimes charges where disproportionality is a key element.

On-site forensic analysis is also highly risky.

“Prosecutors and investigators go to the crime scene after the shelling to gather the remnants of the missile, to talk to people,” Borisenko said. “Russians understand that, and there were cases when they deliberately targeted the crime scene again.”

One police investigator has been killed and several wounded in such strikes, with casualties also among rescue workers.

In some areas, mines can also pose a major obstacle. Where de-mining may destroy evidence, investigators may have to risk starting work without waiting for clearance, Borisenko continued.

Amid such challenges, the workhorse of war-crimes investigations has been the Kharkiv regional police.

“My job and my activities, and those of my department, have significantly changed,” explained Sergii Bolvinov, 41, its head of investigations.

“On February 24 [2022], we woke up because of the explosions, and we accepted the collective decision that we were not leaving Kharkiv because of the war. Our main task now became to document and establish cases for everything that is going on.”

Located 30 kilometres from the Russian border, Kharkiv is Ukraine’s second city, and suffered severely in the opening stage of the war when a substantial proportion of the population fled. The city’s main municipal building took an enormous hit from a cruise missile, and thousands of residential and business properties were destroyed or badly damaged.

Bolvinov oversees a staff of 1,000, with more than 20 investigative units covering every Kharkiv district. A war crimes unit of two dozen was established late last year, although the whole department is involved in investigations, especially in frontline areas.

With the de-occupation of swathes of the region last September, police undertook the process of registering a vast trove of evidence in effectively lawless zones.

“Our big challenge was to keep all the documents for criminal cases on the occupied territory,” he Bolvinov continued. “We needed to keep safe the evidence of the regular criminal cases, murders, rapes and robberies, and then we understood that we needed also to keep the evidence about war crimes.”

Such documentation is essential in building war crimes prosecutions – proving chain of command, confirming specific orders and assessing the use of weaponry.

“We found Russian documents with lists of targets and saw no evidence of them choosing the weapon depending on the surroundings,” noted Borisenko. “They were selecting the target and then using non-precision weapons to hit not only the target but everything around it.”

Amid this, international support and the investigators’ own developing expertise has been critical. Picking up an iPad, Bolvinov showed off a dedicated system created to categorise evidence and share it across the department and other services.

More than 100 bags of documents seized during de-occupation, many hand written, have been entered into a massive database. Search terms can be a surname, a nickname or a location.

Social media also has a key role. Police have established a Telegram channel as a globally accessible most-wanted list where hundreds of photographs of suspects are posted. Building from witness evidence, and accessing publicly available images from Facebook and other sources, the channel enables people in Kharkiv and elsewhere to provide information to the police.

DNA evidence is another critical tool, with the benefit of a central lab and mobile units provided by the Buffet Foundation.

“When we collected all the bodies [from Groza], people started coming to us, telling us that there has to be my relative here, but I don’t see his body,” Bolvinov said. Police continued to remove pieces of the destroyed building to locate human remains, calling on the help of trained sniffer dogs. “We then took DNA from all these body parts and for five days criminologists and DNA labs worked 24 hours a day.”

Matching these results with samples from relatives, they were able to confirm the total number of dead at 59, including an eight-year-old boy, with a further five wounded.

In Izyum, faced with the unidentifiable remains from grave number 319, investigators used a DNA sample to match the body with Vakulenko’s father. This enabled them to confirm photographs taken by cemetery workers of the body from where it had initially been thrown by the side of a road.

Investigators then identified the bullets to provide a cause of death and found witnesses to the writer’s abduction. Matching testimony to photographs, they have now identified the alleged perpetrator and his accomplice, a commander, also implicated in murdering three other civilians.

Despite the challenges, such breakthroughs help investigators remain highly motivated, driven by the horrors they have witnessed, not least at Izyum.

“To see so many murdered people in one location shocks every person with normal values,” Bolvinov said. “I was present every day when bodies were being exhumed. The feelings I had, the feelings the investigators and the criminologists had when they were doing their job, all these feelings will stay with us until the end of our lives.”

Translation and additional reporting by Mykhaylo Shtekel.