Kherson’s Resistance to Russian Occupation Continues

The southern city was the first to fall, but thousands of people are confronting Moscow’s tanks and soldiers.

Kherson’s Resistance to Russian Occupation Continues

The southern city was the first to fall, but thousands of people are confronting Moscow’s tanks and soldiers.

Mass protests against Russian troops have continued in Kherson since the southern port city was occupied on March 3, signaling that Ukrainians’ resistance to invasion may not stop once Moscow takes control of urban areas.

Thousands of people have confronted Moscow’s tanks and soldiers, waving the yellow-and-blue Ukrainian flag and singing the country’s anthem, since Kherson became the first large city to fall into Russian hands.

The resistance has spread to towns across the region, with similar acts of defiance in Nova Kakhovka, Kakhovka, Henichesk, Tavriysk, Novotroyitske, Chaplynka and elsewhere. Invitations to accept aid distribution from a Russian humanitarian convoy were ignored en masse, with residents telling soldiers that no one would take their products.

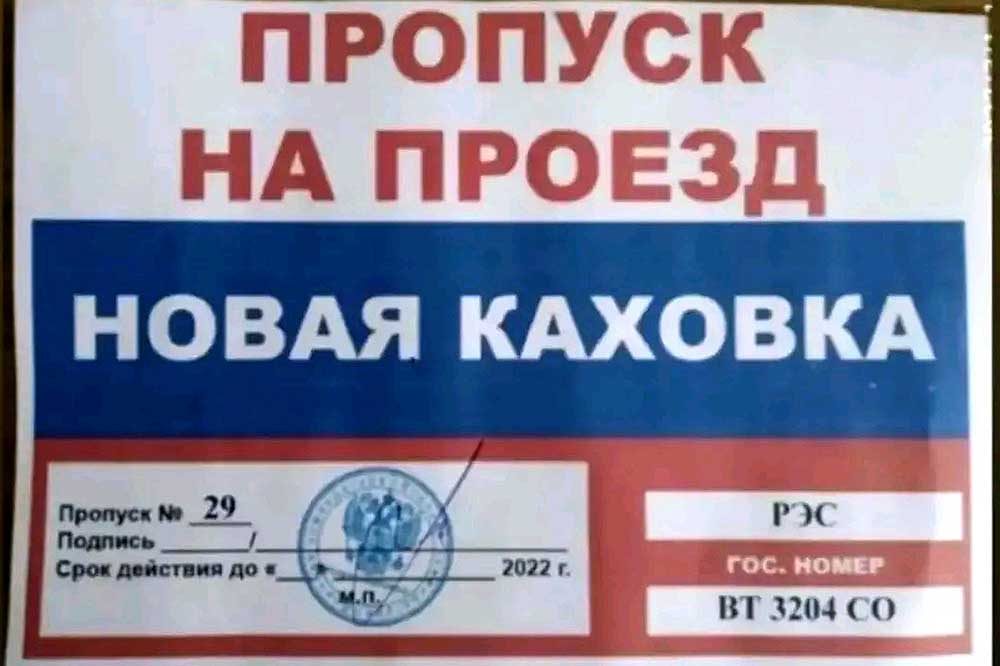

On March 6, Russian troops entered the city of Kakhovka, setting up checkpoints. In neighbouring Nova Kakhovka, Russians occupied the building of the city council and set up a military commandant’s office. Only those with travel passes issued and sealed by this office can enter and exit the town. Residents have taken to calling them ausweiss, like the ID card issued by the German occupation authorities in Ukraine during World War II.

There seem to be two parallel realities in the region, locals report.

“On the one hand, there are Russians in the city council of Nova Kakhovka and in Kherson’s regional military administration,” Serhiy, a resident of Nova Kakhovka, told IWPR. “On the other, next to them, the offices of the mayors of Kherson and Nova Kakhovka continue to operate. It seems like we are the occupiers here and not the Russians.”

A port city at the mouth of the Dniper, Europe’s fourth-longest river, Kherson is strategically important for Moscow. The Kremlin is thought to be aiming to cut off Ukraine’s vital link to the Black Sea and international shipping, with Russian troops are amassing towards Odessa, another key port. Should the city fall, Moscow could build a land corridor along the coast, stretching from its border through Crimea - occupied by Russia since March 2014 - and all the way to Romania.

Kherson’s city council reported that at least 46 civilians were killed in the first two days of the occupation. Russian troops also reportedly shot 16 individuals fighting with the territorial defence. The exact number of casualties and injured in the region remains unknown. On March 1-2, Russians fired at cars and residential buildings in Kherson, including in the Tavriysky neighbourhood. Three kindergartens, six schools and one high school were damaged.

“Such actions pose a direct threat to the life and health of the civilian population, contradict the norms of the international humanitarian law, namely Articles 51, 52 of the Additional Protocol to the Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949, which clearly prohibit attacks on the civilian population and civilian objects,” read a statement by the regional prosecutor’s office. The office opened criminal proceedings for violation of the laws and customs of war after Russians fired cluster munitions from military aircraft into three residential buildings in the village of Chornomorske on March 1.

On March 5, RosGuards, special units of the Russian National Guards, arrived in the region and have detained over 400 Ukrainian citizens in four days, according to the general staff of the armed forces of Ukraine. RosGuards are not deployed in combat operations but have policing functions.

The humanitarian situation remains critical. Russian troops have seized the Kakhovka hydropower plant near Kherson and blocked almost all local roads. The village of Vesele, close to Kakhovka HPP, was seriously damaged by the shelling against the plant and left without power for ten days.

“They no longer shoot Russian ‘grads’[but] the shooting continues every day,” Ljudmila Annas, the village head, told IWPR. “About 30 per cent of the 2,500 residents were evacuated to Nova Kakhovka. People bury their loved ones in the gardens: the occupiers do not allow them to go to the cemetery in a neighbouring village. They are everywhere in the village, they mined the local winery of Prince Trubetskoy and many other objects. Explosive remnants are scattered around the village.”

On March 6, mobile phone communications across the region were restored, two days after Russian troops had disabled Kyivstar and Vodafone, Ukraine’s two largest mobile providers.

“We are facing a humanitarian catastrophe: there are fires, but rescuers cannot go in to help due to the shelling, there are many cases of looting, it is impossible to get to the corpses of those who died in the fighting,” Hennadiy Lahuta, head of the Kherson regional military administration, told IWPR, adding that cars and mobile phones were being looted as well as the contents of local shops and warehouses.

There is an acute shortage of medication and hygiene products across the region, while food and fuel supplies are dwindling in some towns and small villages. Russian troops have been reported stopping cars delivering bread in isolated hamlets. Kherson, Kakhovka and Nova Kakhovka have asked for humanitarian corridors to be opened, to no avail.

“People look for food. We have to queue up to three hours for one loaf of bread. Cash is running low, mobile and internet connections are disrupted, so it is not always possible to pay with a card,” Kakhovka resident Svitlana told IWPR. “People are very concerned. However, after two large protests that were held in our city, I feel less anxious. I saw that I was not alone, that people do not want to see the occupiers on our land, we do not need ‘Russian peace’ here.”

The Russian blockade is also augmenting environmental and public health concerns. The mayor of Chornobayivka, a village just outside Kherson, is negotiating access to the village, home to one of Europe’s biggest poultry farms. The regional administration stated that the giant structure, cut off from the electricity system, was at risk of a severe outbreak of disease as the Russian military had refused to allow in food supplies for the estimated three million chickens. The village’s mayor is negotiating the possibility of selling meat and eggs to the troops.

This publication was prepared under the "Amplify, Verify, Engage (AVE) Project" implemented with the financial support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Norway.