Gaza: “Everyone Has a Family in Danger”

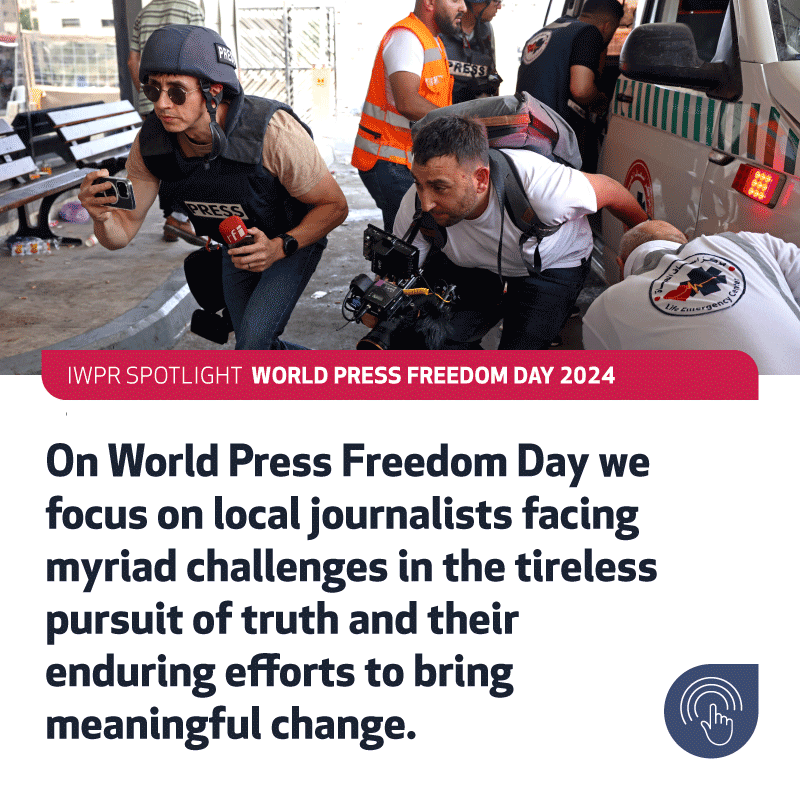

How local journalists cover the story amid intense physical and mental peril for themselves - and their loved ones.

The war in Gaza has had a devastating impact on the Palestinian journalists struggling to cover the conflict. Nearly 100 have been killed, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Suhaib Salem, Reuters head of visuals in Gaza, told IWPR managing editor Daniella Peled about the challenges of working to ensure professional coverage of the war while trying to keep colleagues and their families safe. He was evacuated from Gaza in late December 2023 but continues to cover the conflict.

What have been the hardest aspects of covering this conflict, both in terms of physical danger and psychological harm?

The biggest challenge for us all was having to cover the war while looking after our families, while we were all in danger.

There are no basements in Gaza to hide in. I have six children, aged from 17 years-old to nine months. My family stayed at home while I spent my days at the office. They would call all the time and tell me, “We’re scared, the shelling is very close”.

“You need water to drink and food to eat if you want to carry on reporting.”

What was most difficult was when they heard news about journalists being killed, then they would worry about me. I heard about families being killed and I would worry about them. The fear affects all of us. My team was facing the same situation; everyone has a family in danger.

We also had problems with comms from the first day of the war. The electricity was completely cut, so we needed to find alternative ways of continuing to report. If our cars didn’t work, we used bicycles. We couldn’t use generators because there was also no fuel, so we used solar panels which we moved from place to place.

Then, when we needed to cover the plight of the displaced people in central Gaza - we had run out of fuel, the trip was very long and the road had been destroyed - we found a donkey.

We looked after him like a member of the team – we protected him, found food and drink for him. He pulled our equipment and three members of the team in a cart. We used him for a month and kept him around even after that. We became friends. We called him Zaki, which means smart in Arabic, because he was doing exactly the job we asked him to. Without this donkey pulling a cart, no one would have seen what was happening to the people in the centre of Gaza.

What steps were you able to take to help your team in Gaza stay safe and continue to report in such an extreme situation?

At Reuters, we always plan our coverage and for the challenges we expect to face in Gaza in terms of coverage, security and professionalism. Before October 7, the main challenge was ongoing fighting, with sometimes a bombardment, sometimes a truce.

On the early morning of October 7 I was swimming in the sea with my kids, like I do every Saturday morning. Suddenly I saw one or two rockets overhead, but we are used to rocket fire. Then big numbers of rockets started flying from Gaza towards Israel and I realised something serious was going on. We rushed out of the water and I grabbed my phone and made a couple of short videos of what I was seeing. Then I called my team and said, I think something big is happening.

“The local team is doing exactly the same work as foreign journalists would. We work professionally.”

We went into action and moved to where we had agreed to meet in case of a crisis, in the office and a couple of other locations. No one expected what happened on October 7, but we were as prepared as we possibly could be.

I lead the team both in terms of editorial and in safety. Before any assignment we talk it through, considering and discussing the risks before deciding if it is possible.

I kept in touch with everyone before, during and after. We were always trying to ensure we had a Plan B at all times. This could include using an armoured car, avoiding crowds, border areas, active fighting and bombardment.

We tried to stick to the locations where Israel was aware we were, as an international media organisation. We did not rush to areas of air strikes because of the double tap danger – there would be an air strike, and then 10-15 minutes later the same target would be struck again.

We had remote cameras set up to go live in two different directions, so we could film safely.

We faced the wars of 2009, 2012, 2014, another two years ago, but I’ve never experienced such a situation – in terms of danger but also communications being down, lack of electricity and fuel, the shortage of basic supplies.

After all, you need water to drink and food to eat if you want to carry on reporting.

In the second week it became clear that if we didn’t relocate from Gaza City to the south then we would be in more danger. I called Reuters editorial leadership and said, I think we need to move. We ended up in Khan Yunis, around 70 people – eight Reuters employees with our families. We needed to think constantly how we could both cover the war and provide food and water for our loved ones. One of our staff members was injured, some of us lost family members – all the team lost their homes, their belongings, their friends, their loved ones.

From Khan Younis we were displaced four or five times until we reached Rafah.

What would you say to those who decry the ability of local journalists to report professionally when they are so much part of the story?

The local team working for Reuters is doing exactly the same work as foreign journalists would. We rely on telling the truth. We work professionally and it is very important to have these rules.

My home is Gaza. I am a Palestinian refugee, I grew up in Gaza, went to a UN school and studied at Gaza university. My team are also Palestinian.

We still have a team working in Gaza.

We have a team in Israel too. We all carry out our duties professionally. The Israeli team report what’s happening in Israel, the Gazan team what is happening in Gaza. We are all under one editorial umbrella and working to cover the story.

What has proved useful in terms of psychological support for you, your colleagues and family members?

Psychological safety is very important and we try all the time to include it.

Our reporters go to hospitals to cover the aftermath of bombings, they see injured children, people dying. We provide daily support to help them deal with the impact of this. It’s too much, what we see. And it’s not for one day, or one week, it’s for 200 days now.

Mental health is very important for the team to be able to continue their work. We have access to CiC [the Reuters global counselling service, available to staff and their families]. We spend a lot of time together, we calm each other down, and we insist on the rotation of duties. We assign team members to do a human story on one day, breaking news on another or on simply to look after their family. This is very important: at least one day a week away from coverage.

For those of us who are no longer inside Gaza, the war still has a psychological effect on us. It’s our homeland; our families are still there. We never switch off. But we also want to continue; this is part of the work.

This conflict has seen a huge amount of disinformation spread across multiple platforms. What is the role of visual journalism in combatting that?

You cannot make everyone happy, and I don’t look at social media. We follow our editorial guidelines and focus on facts. We do our best to report. You need to answer to yourself and your team and we swear to report the facts and provide real coverage. I am doing exactly what I need to do.

Palestinian journalist Suhaib Salem has worked for Reuters for 25 years covering life in Gaza and conflicts around the world. He is now head of visuals for Gaza.