Pressure Builds on Central Asia Media

Freedom of speech in Central Asia has deteriorated in recent years, with fresh restrictions on media and bloggers alike and a growing number of criminal cases initiated against journalists.

Here, editors of media outlets from each of the five countries in Central Asia lay out the challenges – and opportunities – they currently face.

Kazakstan

In his 20 years at the Uralskaya Nedelya [Uralsk Week] newspaper, veteran Kazak journalist Lukpan Akhmedyarov and his team were targeted by lawsuits and arrests. In 2011, Akhmedyarov was detained for five days over his opposition to the extension of then-president Nursultan Nazarbayev, and the following year he survived an armed attack. Now working on the Just Journalism YouTube documentary project, he noted a growing pressure on the media to self-censor.

Which political and social events have most impacted journalists in Kazakstan?

Lukpan Akhmedyarov: Journalists’ attitude towards the audience used to be paternalistic… the legacy from the Soviet Union when the press was the voice of state ideology propaganda. Currently, the press is not the leader, and a journalist is not the one who shapes public opinion. With the emergence of the internet, journalists began to get feedback. When you read hate comments organised by authorities via troll farms, it is one thing, but it’s another when you get real people’s comments and they bring you as an author to senses.

“The media space has been undergoing state cleansing for years.”

The media space in Kazakstan has been undergoing state cleansing all these years. Authorities have made 90 per cent of regional and central press dependent on public information contracts. Journalists began to leave such media outlets and create their projects.

What challenges do journalists face?

One of the challenges is the intention of authorities to introduce censorship and make journalists self-censor just like in the Russian media. For example, if we use the words ‘our president’, ‘head of our state’ regarding the authorities, the journalism will end right there, and we will have public relations instead. It is crucially important to me to test myself to check that I am not one of the voice of authorities.

“The state propagates different forms of the same voice of propaganda.”

It is cynical for the state to assure us that it creates all conditions for the freedom of speech in Kazakstan. Saying that several TV channels funded by the state means diversity is like saying that diverse species of segmented worms means biodiversity. The state propagates different forms of the same voice of propaganda: talk shows, themed programmes that at the same time broadcast news, yet all newscasts are rewritten press releases.

What challenges and opportunities does Kazak journalism face, especially in terms of the changing media and political environment?

The Kazak-language media has gone a difficult yet impressive way over 30 years. There are now publications that issue economic reviews, analysis and political reviews in the Kazak language.

We have to go through this linguistic division and then we will come to unity. If we look now what the Russian and Kazak-language press write about, they write about different themes and issues. It will take some time before both audiences become concerned about the same issues.

More young people are becoming interested in journalism. Journalists of my generation have a warped conception of journalism as a social benefit which they access but which is distributed unequally. We used to choose profession as a way of making a living, but now that is not the point. The point is what should be done to make real change.

Kyrgyzstan

For the last decade, the Kyrgyz-language Politklinika newspaper has earned a reputation as a serious, independent journalistic outfit. However, in recent years it faced a series of legal challenges, most recently in January 2024 the arrest of 11 of its journalists. Editor-in-chief Dilbar Alimova said amidst detentions and growing legal restrictions, Politklinika would continue its work.

Do you feel that the stakes for independent journalism have got higher?

Dilbar Alimova: It became very dangerous for journalists - and for all citizens - to criticise the authorities. In practice, it is obvious that anyone can be detained. Independent journalism is facing hardship and difficulty; it is unknown whether it will survive. Journalists must do their job without hindrance. Authorities must obey the law and ensure the rights secured by the Constitution.

“It became very dangerous for journalists -and all citizens - to criticise the authorities.”

Unfortunately, freedom of speech has been under pressure from all administrations [since independece], but the current government performs it by sophisticated, unprecedented methods. These are tough and illegal, with attacks from all sides.

The gradual adoption of laws allowing censorship, ongoing cases against every media outlet, arrests of journalists, activists; we have not seen such pressure for 30 years.

The arrest and detention of 11 journalists in one go was record-breaking. We have never seen such a thing before.

Have you ever thought that it was not worth it?

Our office has faced a series of attacks. We have had lawsuits, complaints to block our website, a journalist in prison [later released to house arrest]. However, we know that our journalism is conscientious, we have done nothing wrong to the state, we work according to international standards and journalistic ethics.

“Media outlets criticising the government have almost disappeared.”

Let me emphasise that we are journalists, not enemies of the state. On the contrary, we help authorities to detect corruption schemes, create materials protecting the security of the state, work to improve people’s media literacy skills. Journalists are helping the authorities and I want the authorities to realise it.

How will the current purges against journalists and bloggers impact media?

Pressure pays off. Some media outlets have to sell their shares, while others use self-censorship. I will not name names, but I can feel self-censorship in private talks or in content of materials. Journalists are frightened of expressing themselves on particular issues or about ‘sensitive’ subjects. Media outlets criticising the government have almost disappeared, and this is very bad.

Tajikistan

Freedom of speech and access to information in Tajikistan has steadily worsened. Journalists are routinely prosecuted and imprisoned, while very few independent outlets dare criticise the government.

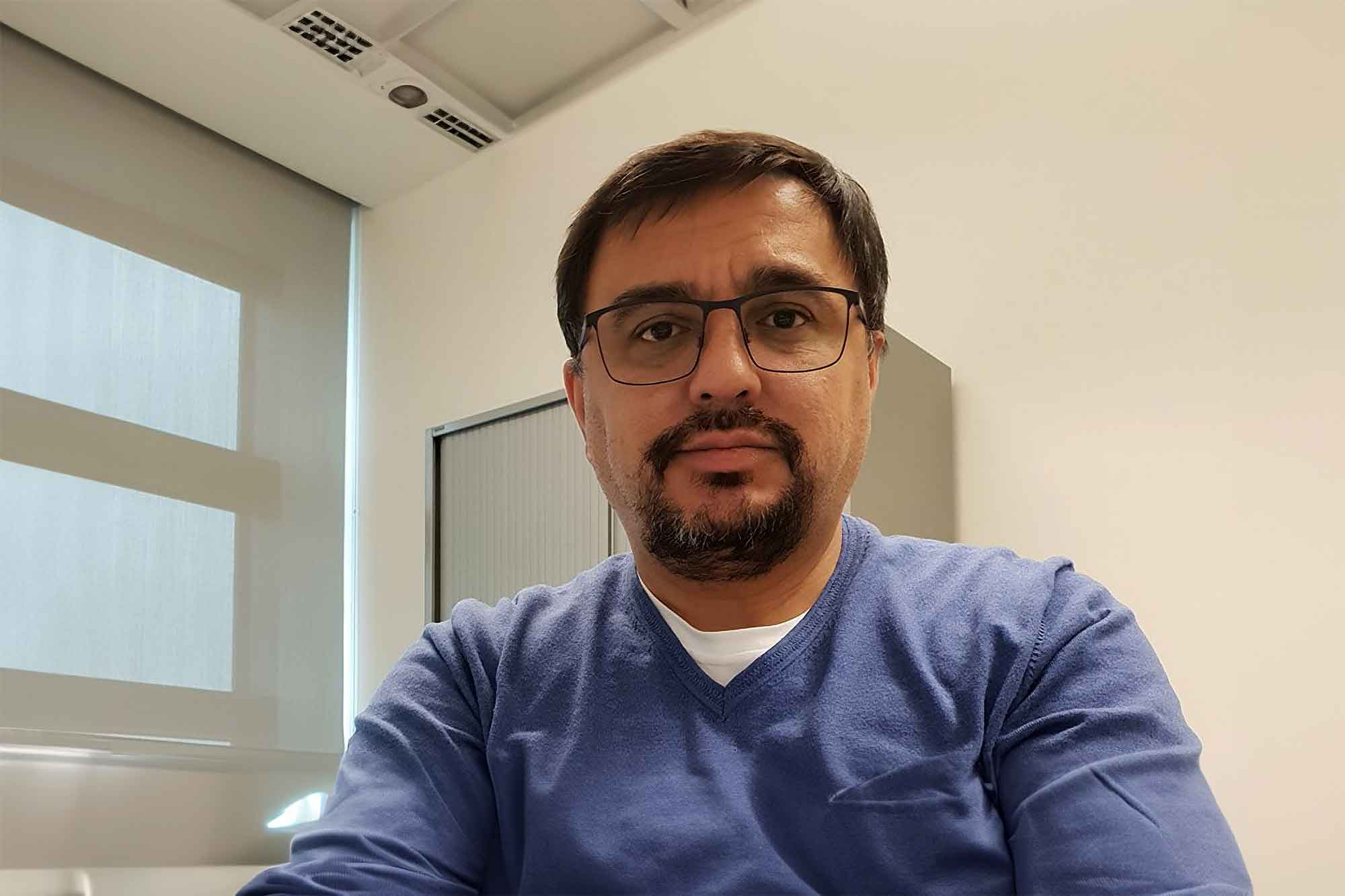

Bakhmanyor Nadirov, editorial director of Asia-Plus, one of the leading news agencies in Tajikistan, said that he nonetheless remained confident that journalism could be a force for positive change and hoped that the authorities would stop treating the media as enemies.

How would you evaluate Tajik media today as a manager and a journalist?

Bakhmanyor Nadirov: Tajik independent media are in a complex situation: their financial state is unstable and the authorities keep on pressuring them. Self-censorship is rising, access to information gets worse and the list of taboo themes becomes longer.

I mean only independent media because Tajik state media are fine: they are funded by the budget, have good profits from subscriptions of state-funded organisations and commercial advertising from state TV channels. They are not allowed to write about many topics, just like independent media, but it suits them.

“Self-censorship is rising and access to information gets worse.”

The activities of foreign and private independent media are restricted, and they face problems of accreditation.

The activities of Tajik bloggers have also recently come under strict state control. Like traditional media, they face restrictions that influences their freedom of expression.

How freely can current affairs be covered?

Tajik media and journalists have almost no freedom now. A couple of independent and foreign media still try to cover the situation objectively, but they cannot do it fully. They prefer to produce easy content: they publish official news, tells stories of interesting people, write about culture, etc.

Independent media rarely publish critical materials about official policy, government activities, corruption or other negative events.

“Media owners do not want to lose their business and journalists do not want to be in prison.”

As to world news, there used not to be special bans on coverage. But in the last two years, security agencies have tried to control such themes, too. In the very beginning of the war in Ukraine, representatives of these agencies ‘recommended’ the media to not cover events. As a result, independent media rarely write about the war, and if so they do it with caution.

Self-censorship has also risen in recent years. The reasons are prosecutions, intimidations and prison sentences, as well as the closure of private media. No one wants to be another victim: media owners do not want to lose their business, journalists do not want to be in prison.

How would you describe the ease of access to sources of information?

Access to information has become much worse. It was previously difficult to get data for analytical materials and investigations; now journalists have to spend much more time and effort to get publicly available information confirmed.

As to official requests, journalists often wait for a response for several months, only to get formal or unclear, incomplete answers. The media and journalists almost never recourse to court appeals for fear of troubles with state bodies. Many try to avoid any confrontation with authorities.

Some legal amendments are being prepared, with fears they will further worsen the situation.

Parliament is planning to pass the information code, which will incorporate several laws, mainly about access to information. I can confirm that the code draft has some provisions that potentially worsen the situation with the media and access to information. Media representatives have already made their recommendations to improve the points in issue. However, it is still unclear what version of the code will be adopted.

Which measures can be taken to improve freedom of speech?

Compliance with existing legal acts could significantly improve the situation of the media in the country, even without the introduction of new amendments or measures. However, the authorities seem not to follow them and they are not interested in improving the situation. Improvement can occur if authorities stop treating private media and journalists as enemies and start cooperating with them.

Uzbekistan

Despite reforms carried out by President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, the authorities continue to largely control the media in Uzbekistan.

Lola Islamova, editor-in-chief of the Anhor.uz news agency and chair of the Centre for Contemporary Journalism Development of Uzbekistan, said that pressure on the media continued to mount.

How do you evaluate freedom of speech in Uzbekistan?

Lola Islamova: The main issues faced by media outlets in Uzbekistan are self-censorship and financial instability. The size of the country’s advertising market was estimated by experts at nearly 78 million dollars in 2023. However, a considerable part - nearly 68 per cent - of this budget goes to television advertising.

“Editorial offices cannot be independent if they are financially unstable.”

Editorial offices cannot be independent if they are financially unstable. It is difficult to hire qualified staff and produce quality journalism.

Some international human rights organisations believe that free speech has worsened compared to the first years of the current president’s rule. What are the reasons for that?

Freedom of speech was taken in Uzbekistan as a chance to express opinions freely after a long time of restrictions, not always in compliance with legal frameworks, the rights of other people and personal boundaries. As a result, some materials spread online, often by bloggers, went beyond code of ethics and legislation. In response, those who were criticised started to take measures which were interpreted as restriction of freedom of speech.

“An independent judicial system as it plays a key role in protecting the rights of journalists.”

Moreover, when information concerns particular interests or discloses corruption or violation of laws, journalists and bloggers can face pressure. It is a widespread practice that cannot be justified. So, our editorial office follows the rule, ‘Write like it is going to be checked by a prosecutor tomorrow.’

What are the main problems faced by independent media?

Pressure exerted on journalists often becomes a matter of litigation. There is a lack of legal literacy among journalists, and high legal fees which makes qualified defence and counsel unaffordable. That is why it is important to have an independent judicial system as it plays a key role in protecting the rights of journalists.

There have been cases of pressure on bloggers and journalists, especially when they cover sensitive issues or criticise authorities or private entities.

In 2023, my editorial office faced a lawsuit that lasted for seven months, related to the publication of material containing analysis of the operation of a monopolistic company. The company filed complaints to the ministry of interior affairs about defamation and damage to business reputation.

The situation changed only after the case received widespread publicity, which made the company withdraw its complaints.

This case emphasises the importance of protection of freedom of speech and journalistic independence, as well as decent legal assistance to media under pressure.

Journalists can perform their professional duties if they have relevant knowledge and skills, including understanding of journalistic standards, methods of information collection and fact-checking.

Tools are not just technical means to collect and distribute information, but also access to legal databases, the expert community and other important resources. We have problems with this; not all state bodies publish information on time and in full and we often have to buy data from the statistics agency.

Financial stability is required to ensure the independence of editorial staff from political or commercial pressure. It also lets journalists focus on their job, without wasting their time on searching for other means to make a living.

State protection is a key aspect because it contains both legal assistance of journalists’ rights and ensuring their physical security. State protection can also be in the form of passing of laws contributing to transparency and availability of information. We do not have it so far.

Can you point to any positive developments?

A considerable achievement has been strengthening the civic engagement of journalists and bloggers. Journalists began consolidating more actively when they saw that the protection of their rights was not only the state’s obligation but also in their personal interest.

A legal clinic has been operating in the Centre for Development of Contemporary Journalism for over four years. Any journalist or blogger can get advice there. It creates an environment where journalists can feel more protected. Moreover, unity can serve as a powerful tool of protection of the freedom of speech. Journalists started to self-organise, which marks a breakthrough.

Turkmenistan

Radio Azatlyk, Radio Liberty’s (RFE/RL) Turkmen service, is one of very few outlets covering the situation in Turkmenistan.

It has worked in the country since 1953, although its editorial staff have never obtained accreditation. Farruh Yusupov, Radio Azatlyk head for the last eight years, said that their correspondents could work more or less openly until 2018 when many were forced to stop their work or go underground.

What are the conditions like for media and journalists in the country?

Farruh Yusupov: Turkmenistan has not had freedom of speech, including freedom of the press, for a long time. There are no independent journalists working openly in the country. Our correspondents, just like correspondents of other independent outlets, work underground. As far as I know, there are no journalists from the international media there. There used to be correspondents of Reuters and AFP, but there have been no publications from them for a long time.

“There are no independent journalists working openly in Turkmenistan.”

Since 2018, we had to ask all our correspondents to go underground as it became very dangerous to work there. They risk physical assault, and both correspondents and their relatives received threats.

How narrow are the limits of what may be said about domestic and global events?

The government press, pro-government and so-called quasi-independent outlets reflect all the current events covered by official sources. They publish uplifting news from the outside world – novelties in technology, cultural events, etc – but not cover political topics, even the ones that take place outside the country.

For example, one of the major events in recent years is the war in Ukraine. Not a single government agency, or pro-government agency has reported the ongoing war so far. It’s as if it does not happen, or as if it is not important for the public of Turkmenistan.

“Not a single government agency has reported on the ongoing war in Ukraine.”

Or political events such as elections in Russia or in Turkey. Turkmens discuss it privately. The municipal elections in Turkey last month are actively discussed in private talks, on social media. But the fact that the pro-government party lost the municipal elections was not reported in the press.

Sometimes, official outlets publish messages that the president of Turkmenistan congratulated his Russian colleague on the electoral victory. And people reading the government press can learn from such messages that elections were held in Russia.

We certainly try to report everything. We publish the latest news about Ukraine every day and generally try to cover events in Turkmenistan. As you know, the country has been in an economic crisis for seven years – the standard of living has dropped, people cannot afford essential goods – bread, flour, vegetable oil.

If natural disasters happen in the country, government press does not report them. We try to keep our public up to date on the most important events taking place in Turkmenistan.

Do you feel pressure from the government on your staff, particularly on your authors within the country?

We certainly do. For safety reasons, I cannot specify or give examples of how authorities of Turkmenistan persecute journalists, but they do. Police and security agencies try to detect people who speak to us, provide information, tell about events they have witnessed. These people are at risk of serious consequences. Therefore, our correspondents work underground, we do not provide their names.

Unfortunately, we cannot publish photos or videos they send to us because there are surveillance cameras installed in many towns, districts and even villages. We only publish photos or videos when we are 100 per cent sure that it would not carry consequences for our sources or correspondents.

When we cover any event taking place in Turkmenistan we try to contact the authorities for comment. Once they hear it is a Radio Azatlyk correspondent, they put the phone down or often start swearing.