Why Local Voices Matter

The real heroes are those on the ground, fighting to bring truth to light.

Ten years ago this winter and spring, I crisscrossed North Africa and the Middle East observing revolution after revolution. Staring in Tunis with the Jasmine Revolution, I made my way to Egypt, Libya and finally Syria, where I went back and forth over several years reporting the war and the human rights abuse against civilians. The culmination was my book, The Morning They Came for Us, which chronicles, more or less, what happens when your strive for freedom and democracy and then you are brutally punished for it.

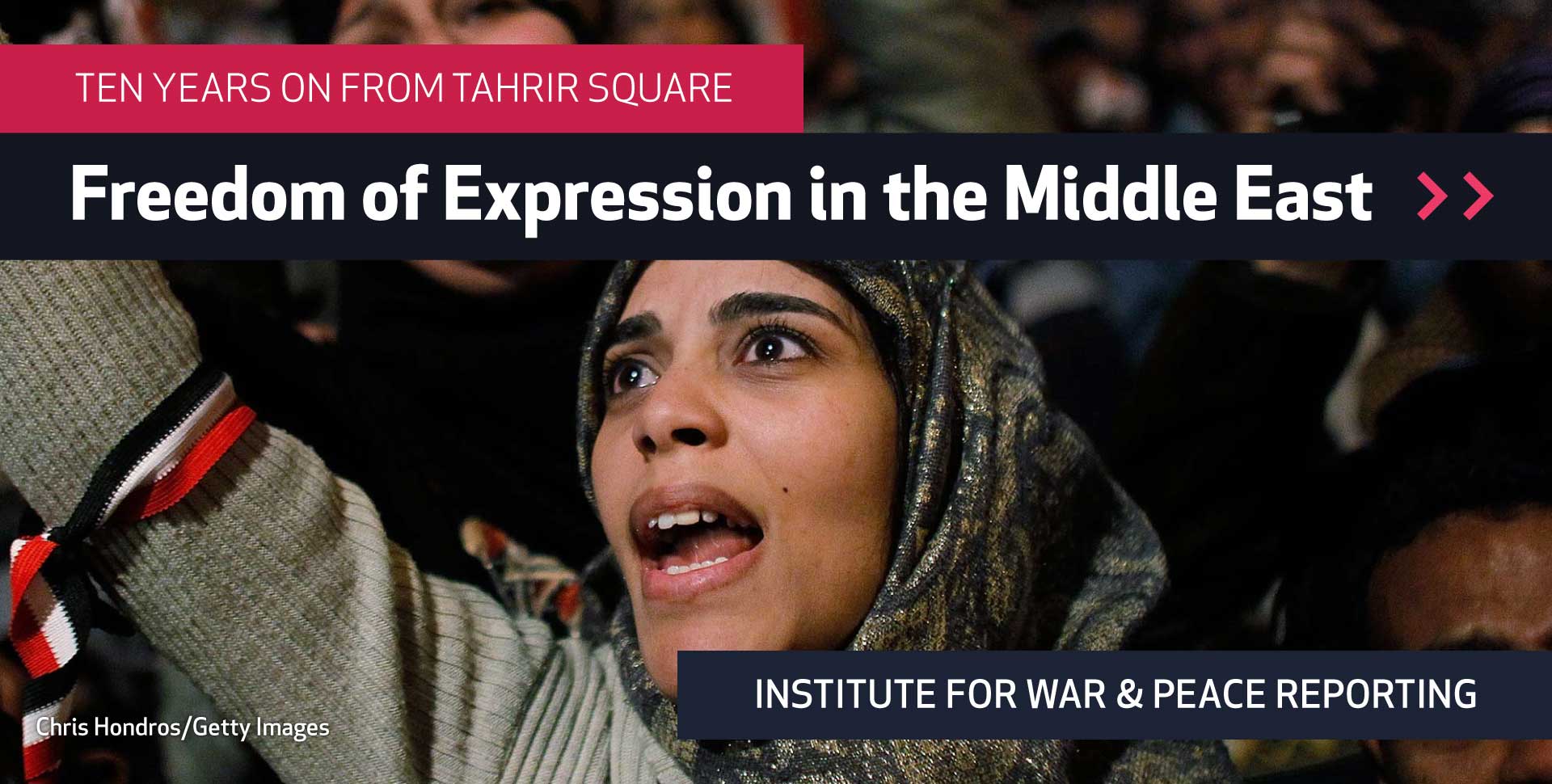

But back in 2011, it was a revelation to see thousands of people marching for freedom. Each demonstration, each revolution was different but there were common themes. The main rallying cry from the crowds in Tahrir Square or Ben Ghazi or Homs or Aleppo or Tunis was always the same: we want our freedom.

Always, when I think of press freedom I think of my colleague Jamal Khashoggi, murdered by henchmen under the order of Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia. Jamal’s work is not over – it lives on in the spirit of every reporter working to bring truth to light.

It was exhilarating. Crowds were rising up against decades of dictatorships, of corruption, voicing their frustration at the lack of opportunity. What they wanted was the right to speak and write and live in accordance with their personal liberties.

As someone who grew up first in North America, later in the UK and France, freedom of speech was a tenet of human rights I took for granted. Not so for my colleagues in Tunis who had to work underground with white-hat hackers like Anonymous to overthrow Ben Ali’s ministry of information and get their messages out. Not so for my Syrian colleagues in Aleppo or Damascus who risked everything to plead for freedom, and if they were caught, were thrown into prison and tortured or killed. Or my Egyptian friends who were tortured in prison and stripped of all rights.

What the authorities want to say is, “It's dangerous to speak out”. The number of the missing in Syria, the number of imprisoned in Egypt is enormous: many of them are our comrades and colleagues who tried to express and explain what was happening. These activists and journalists are what their repressive governments say is a threat to “national security”.

Ten years on, what have we learned? Egypt under General Sisi remains even more repressed and dangerous for journalists than ever. The proportions of journalists attacked in 2020 as opposed to ten years ago is shocking: according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, nearly 27 journalists are imprisoned, two murdered and one missing.

This includes Aamar Abdelmonem, a freelancer, imprisoned in December 2020 on false charges, denied medication in prison (he is diabetic) and his eyeglasses. When I read about the cases of my colleagues who are incarcerated for simply telling the truth, I realize how lucky I am to live in a society where I can write what I choose.

Always, when I think of press freedom I think of my colleague Jamal Khashoggi, murdered by henchmen under the order of Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia. Jamal’s work is not over – it lives on in the spirit of every reporter working to bring truth to light. They are not only journalists but also lawyers, human rights defenders, members of civil society. You might not hear about them – because they are working quietly but with great precision and care. They are my heroes.

As an international journalist, I am forever grateful to the journalists working under the radar in these countries – the ones who risked arrest to meet with me or speak with me or share their experiences or notes, the ones who came to my hotel in Cairo, risking everything, the ones who met me in Damascus cafes under the eyes of the mukhabarat, then saw the security guards and had to flee. The ones on the ground working when the international press cannot.

They are our heroes, our inspiration and above all, our colleagues. We must not forget them – and we must do everything in our power to protect them. Part of the reason I am proud to be a part of the IWPR international board is to spread the word of the excellent work that is done on the ground by my colleagues. In the words of the former senior UN official Andrew Gilmour, now executive director of the Berghof Foundation, we are living in times when the pushback to human rights has never been greater. Which means those of us who can raise our voices louder to protect our friends on the ground must do so, with conviction and passion.

Janine di Giovanni is a Senior Fellow at Yale University’s Jackson Institute for Global Affairs, IWPR international board member and the author of nine books. In 2020, the American Academy of Arts and Letters gave her their highest prize for non-fiction for her lifetime body of work, which largely focuses on human rights.